Why progressive politicians should be going on Fox News

Rep. Ro Khanna shows how left- and right-wing populists might work together on foreign policy.

Hello friends,

This edition of the newsletter has a 6 to 7 minute read time:

(1) I argue that the pushback against progressive congressman Ro Khanna’s appearance on Laura Ingraham’s show on Fox News is off the mark — and that if anything the left should have a more pronounced presence on Fox.

(2) What I’m reading.

Newsletter pro tip: Add this address to your contacts, and in future weeks if you can’t find the newsletter, check your spam folder (mark it as “not spam” if it’s in there) and Promotions tab (drag it into your primary inbox, and hit “yes” when asked to do this for future messages).

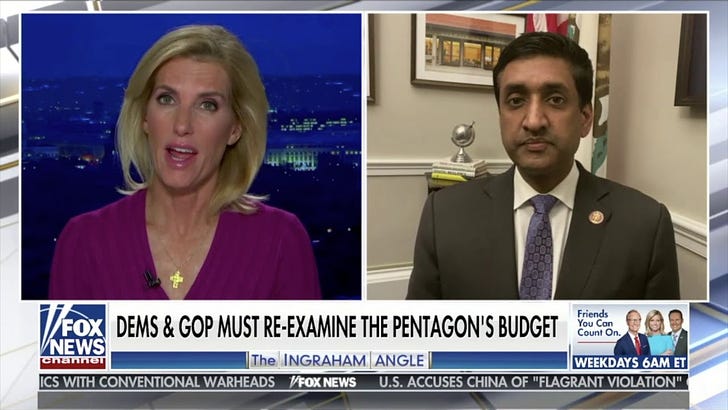

Rep. Ro Khanna’s Fox News appearance on Fox News was a good idea

California Congressman Ro Khanna, a progressive in the Bernie wing of the Democratic Party, caused a bit of a stir last week when he showed up on Fox News host Laura Ingraham’s show to talk foreign policy. His appearance prompted some moderate liberals and progressives to argue that agreeing to be interviewed by Ingraham is tantamount to legitimizing or turning a blind eye to her virulent brand of white nationalism.

I think the debate about the ethics and efficacy of Democrats appearing on Fox News is a healthy one, and requires careful thinking. But on the whole liberals and the left should be encouraging more, not less, of it in the future.

During Khanna’s brief appearance on Ingraham’s show he discussed reducing reckless Pentagon spending and redirecting that money to high-speed internet infrastructure; his alignment with Trump’s initiatives to remove troops from Afghanistan and Germany; and his reservations about Biden’s hawkish defense secretary pick, Michele Flournoy, for her advocacy for escalating conflict in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria.

Khanna argued that he saw opportunity for “bipartisan consensus” in withdrawing from endless and non-accountable spending on foreign bases, and also framed his concerns about interventionism as distractions from competition with China. “China hasn’t been in a war since 1979; we’ve been in 40 wars,” he said. “If you view China is our biggest strategic competitor in the 21st century, then these policies aren’t what’s going to allow America to win and compete.”

His remarks prompted Ingraham to say at the end of the segment: “Congressman Khanna, I would love to have you back, because I actually think there are a lot of issues where … conservatives can work with progressives and this is just one of the more obvious issues.”

You can watch his appearance in full here:

Khanna’s spot sparked a fair amount of criticism among some prominent liberals and progressives.

I very briefly debated the point with NBC’s Mehdi Hasan, and there’s also a good-back and-forth between Hasan and The Intercept’s Ryan Grim here.

After reflecting on the issue, I think Khanna’s appearance was not only defensible, but something the left should build on. Here are some thoughts on why.

(1) Khanna went on with a specific goal of persuasion among an audience that might be receptive to it. This wasn’t a chummy panel of talking heads sharing hot takes, it was an interview tightly focused on the issue of foreign policy before a segment of the Fox News audience that was exceptionally likely to be receptive to his message. Ingraham, like Trump and Fox’s Tucker Carlson, is a white nationalist right-wing populist who has expressed sustained disinterest in playing the role of global police or purveyor of democracy; she has said repeatedly she was wrong about the Iraq War and appears to be interested in scaling back some defense spending.

This was not a conversation in which Khanna politely nodded while Ingraham went on about the evils of immigration, but one where Khanna stated in positive terms what he thinks foreign policy should look like and how he felt that there were some people on the right who might be inclined to join him. Khanna is a politician, and his ability to succeed in advancing his goals involves persuading people to believe in them. He was doing business.

(2) This is one of the very few realms in which the populist left and populist right can actually work together in Washington. For the most part “populist right” is a kind of oxymoron that shares little in common with the populist left outside of an anti-establishment aesthetic. As the Trump era revealed, right-wing populism on a domestic level means substituting xenophobic immigration policies for programs that could actually generate broadly shared prosperity or assist the have-nots in our country — all while assaulting health care and passing tax cuts that favored corporations and the affluent without ever triggering a growth spurt. The populist left is heavily antiracist in orientation; right-wing populists pay their bills with train whistle racism. Since right-wing populism, at least as it manifested during the Trump era, has been about using bigoted culture wars to shield plutocratic policy regimes, even compromise with its adherents is often inadvisable. (The contours of right-wing populism could change post-Trump, but that’s behind the scope of this article.)

But when it comes to foreign policy, there are already real opportunities for targeted cooperation, because this flank of the conservative movement is disinterested in foreign interventionism. Now, most of the ideological underpinnings of their position are of course troubling: the white nationalist warning that if you "invade the world, you invite the world" is part of a broader hostility to cosmopolitanism and globalization that stems historically from antisemitism and other types of bigotry; this movement simply prefers its racial domination domestic rather than imperialistic. (There was some discussion of this on my Facebook page the other day.)

But the consequences of this paradigm are a real and potentially growing contingent of conservatives who are skeptical of the purpose and benefits of an endless web of foreign bases and forever wars. Moreover, the antiwar left has an opportunity to shape the very way that the nascent populist right thinks about war and justice — and can nudge their public logic away from a racialized introversion to, for example, an impulse to think about the right to robust self-determination, or to discuss capital’s interests in expansionism without grounding it in antisemitic tropes.

The antiwar left is of course very small still in Washington and has very little to work with given the Democratic establishment’s continued interest in muscular foreign policy. Biden’s picks of Antony Blinken for secretary of state (who responded to a tweet of mine criticizing his record the other day, incidentally) and Flournoy for defense secretary should not inspire confidence that his administration will avoid an aggressive international posture or foreign entanglements. Moreover, presidents have tremendous freedom in setting foreign policy agendas.

But congressional maneuvering on foreign policy does matter and requires bipartisan action. Both parties came together early during Trump’s tenure to prevent him from being dovish on Russia sanctions, for example. And earlier this year we saw House Democrats teaming up with Rep. Liz Cheney — the daughter of Dick Cheney — to hamper Trump’s efforts to reduce troop levels in Afghanistan. Khanna wouldn’t be setting any strange precedent in reaching across the aisle.

Back in college, I vividly remember doing antiwar activism with radical free market libertarians. They found the pro-labor work that my leftie friends and I did to be amusing and wrongheaded, but on issues of war and surveillance we saw eye to eye. Over meetings and meals, we got to know each other’s ideologies better, and on those issues where we converged we had more bodies — and as a result we were able to make a bigger splash.

(3) I’ve been seeing a lot of concerns about how Khanna’s appearance served to “validate” or “legitimize” Ingraham’s views. I am sensitive to concerns that if it were to become normal for Dems to show up on Ingraham’s show and never challenge her views, that it could ultimately play a role in making them appear less nefarious then they are. This is legitimately tricky and uncomfortable stuff.

But a boycott on engagement with these platforms is an impractical proposal, mainly because Ingraham is already mainstream. She gets millions of viewers a night, and Fox News has been the the most-watched cable news network in terms of both total day and prime-time viewers for 227 months in a row. Her views may not be acceptable among cultural elites, but they are far from offensive to wide swaths of the population.

In an ideal world Khanna would never have to talk to a pundit who probably wishes his parents had never immigrated to the US. But we don’t live in that world, unfortunately. And as 2020 elections showed very clearly, liberal-left mobilization isn’t cutting it when it comes to curbing the power of the right. If we know that persuasion must be pursued as a tactic, then how can the left afford to boycott major platforms that speak to the right?

I’d also say that people with the objection that a dialogue legitimizes the worldview of one’s interlocutor — a claim I disagree with in this case, but can understand concerns about — should contend with the reality that the effect can cut both ways. Ingraham is also opening up right-wingers to left-wing populists by inviting Khanna on to the show.

(4) On this point below, I would simply point out that the U.S.’s involvement in the Middle East isn’t just an existential threat to Muslims, but a systematic extinguisher of Muslim lives.

Withdrawing from theaters of war would have tangible benefits on the existential question, and I believe the antiracist left can still credibly fight against discrimination at home simultaneously by articulating a coherent antiracist worldview.

I say this, by the way, as someone who finds Hasan’s analysis of global Islamophobia to be very insightful — and recommend his discussion with Ezra Klein on the topic.

(5) One must be careful to not conflate Khanna’s appearance with left-wing journalist Glenn Greenwald’s model of engagement with Fox.

Khanna went on the network to talk about a tangible opportunity to advance a progressive goal, while Greenwald often appears on Tucker Carlson to simply, well, own the libs.

If you watch Greenwald on Fox, he’s often not in the business of persuasion or carving out pathways for action. Instead, he’s sharing perspectives on the corruption of the Democratic establishment or liberal media or new Biden personnel which Carlson and his viewers already hold. From body language alone it’s evident that Greenwald’s experiences do not challenge Carlson or raise thorny questions but delight him, and that their shared, organic hatred of mainstream liberal institutions isn’t about building a terrain for potential strategic alliances as much as it is letting off steam.

Obviously anyone familiar with my writing knows that I am also extremely critical of the Democratic establishment, liberal media and Biden. And I respect Greenwald’s impulse to make a point of valuing consistency in principle over party or clique. But going on Carlson’s show to confirm and intensify his audience’s generalized mistrust of left-of-center politics — while often failing to raise a single point about how many of its problems exist on the right, typically in a much worse way — has the effect of limiting left political possibility rather than expanding it.

(6) Khanna’s appearance was reportedly the first appearance on Ingraham’s show by a Democratic member of Congress other than Tulsi Gabbard since 2018. So there aren’t exactly well-established best practices here. I’d be curious to hear from people on how to navigate the ethics of this activity. Should any appearance have a critical component to it, where, for example, a host’s wrongheaded views are explicitly rejected?

What I’m reading

Robert Wright’s “progressive realism” report card on Biden’s defense secretary pick.

Interesting Twitter thread by informatics scholar Kate Starbird on participatory disinformation.

“For the Bernie Sanders wing of the Democratic Party, the Joe Biden presidential transition is what losing looks like. It is also, for better or for worse, what incremental progress looks like.”

“Tenant organizing changes the balance of power. Organizing your building is the first step toward forcing a landlord to patch a roof, or negotiating a lower rent increase, or stopping the eviction and displacement of your neighborhood’s residents. It also creates community, establishing a framework for neighbors to take care of one another, plan for natural disasters and other emergencies, and mediate conflict without police.”

This essay by Columbia scholar Jedediah Britton-Purdy is about “how the politics we live with now took its shape from the long, recurrent refusal of history’s end, about how we are still living with a political vocabulary born in the Long 1990s.”

Biden Wants America to Lead the World. It Shouldn’t. “The Biden team should make solidarity — not leadership — its watchword for approaching the world.”

How Biden’s foreign policy team got rich.

“Over the past decade — and especially since the pandemic cratered the global economy — a funny thing has happened within the world of Big Money: a small but growing number of finance professionals have begun talking like leftists.”

Thanks for reading! If you liked what you read, please forward and share on social media.

If you want to give me any feedback you can reply directly to this email, or like and comment on the post itself using the buttons below.

Not a subscriber? Let’s change that!